Our reviewers evaluate career opinion pieces independently. Learn how we stay transparent, our methodology, and tell us about anything we missed.

Hiring managers don’t promote medical writers because they “write well.” They promote the writers who can own complex documents, survive tough reviews, and protect accuracy under pressure. Here’s the career path I’d follow to get there.

When I first learned what medical writers do, it clicked immediately: this isn’t a “writing job.” It’s a trust job.

If you’re the kind of person who likes digging into source material, writing with constraints, and tightening language until it’s unambiguous, medical writing can be an incredible career. If you hate being reviewed, don’t like rules, or want your writing to feel expressive… it’s going to frustrate you.

I’m going to walk you through the medical writing career path the way I’d explain it to a friend: what the levels really look like, what changes as you move up, and what I’d focus on at each stage so you’re not stuck at “junior writer” forever.

Most careers in medical writing don’t progress just because time passes. You move up when you become the person a team can rely on for three things: accuracy, process, and ownership.

Early on, your value is execution. Mid-career, your value is independence. Later, your value is leadership, either through people management or through being the person who can handle the hardest documents and the messiest review cycles.

Below is the path I’d follow, in order.

“Medical writer” is too broad. If you apply to everything, you’ll end up building samples that match nothing.

If I were starting today, I’d pick one lane for 60–90 days and commit to it. Not forever, just long enough to build credible proof.

Common lanes I see:

Regulatory and clinical writing (protocols, CSRs, narratives) tends to be template-driven and process-heavy. Publications and scientific comms lean more narrative but still demand evidence discipline. Patient education and health content reward plain language and usability.

You can switch lanes later. But if you start broad, it’s hard to look believable.

A lot of new writers assume they need to go back to school to become medically literate.

Sometimes a degree helps, but what you really need early is the ability to read source material without panicking. That means getting comfortable with study designs, endpoints, limitations, and the difference between “evidence suggests” and “this is proven.”

I’d practice by picking one therapeutic area and going deep for a month. Not because you’re locking yourself in, but because depth gives you vocabulary, pattern recognition, and confidence.

If you want one external reference that’s actually useful for understanding how clinical evidence is organized, I’d skim how a Clinical Study Report is structured at a high level. The ICH E3 guideline is dense, but it gives you a feel for the standards mindset.

Medical writing is a professional writing job where the process is the product.

At the junior level, your life is reviews, tracked changes, templates, and “make sure this claim matches the source.” If you can’t operate inside that workflow calmly, you’ll always feel behind.

This is also where people either level up fast or stall out. Writers who treat review feedback as a collaboration tool get stronger every month. Writers who treat feedback as criticism get exhausted.

If you want to see the kinds of questions teams ask to test your process maturity, the medical writer interview questions guide is a good “preview” of what senior writers are expected to handle.

To learn more about medical writing, we suggest checking out our Medical Writing Certification Course.

If you’re early-career, you’re not trying to prove you’ve done everything. You’re trying to prove you can behave like a medical writer.

I’d create 3–5 samples that match the lane I picked, and I’d keep them clean and reviewable. The big goal is to show that you can take source material and produce something structured, accurate, and usable.

If you don’t have access to real internal documents, that’s fine. You can still build strong samples by writing educational pieces, rewriting abstracts into lay summaries, or creating mock deliverables using publicly available studies.

I’d also include a short context paragraph above each sample: audience, purpose, and what you’re demonstrating (plain language, evidence handling, structured drafting, etc.). That single move makes reviewers trust you more because it shows you think in constraints.

At the entry level, your job is not to be brilliant. Your job is to be dependable.

This stage often looks like supporting senior writers, drafting sections, updating documents based on reviewer comments, and learning how a team’s standards work. You’ll be asked to edit, format, cross-check, and keep documents consistent.

This is the stage where I’d obsess over fundamentals that make you easy to work with: naming conventions, version control, comment resolution habits, and a personal QA checklist.

If you’re updating your resume for these roles, the medical writer resume guide will help you frame entry-level work as “evidence of process,” not just “I wrote things.”

[IMAGE: Entry-level medical writer responsibilities]

The jump from junior to mid-level usually happens when you stop needing rescue.

At this stage, I’d aim to own a full deliverable end-to-end, even if it’s a smaller one. Ownership means you can outline, draft, QA, manage reviews, resolve feedback, and ship something clean without a senior writer rewriting the whole thing.

You’ll also start developing your personal “voice” in a medical writing way, which really means consistent phrasing, consistent claims language, consistent terminology, and consistent caution where the evidence is limited.

This is the point where I’d start tracking my wins. Not for ego, but for leverage. If you can say “I reduced revision cycles” or “I improved consistency across documents” you become promotable.

Senior medical writers aren’t just faster writers. They’re the people teams trust with the hard stuff.

At the senior level, you’re often dealing with complicated inputs, conflicting reviewer feedback, tight timelines, and stakeholders who disagree on what the document should say. The writing is still important, but the real skill is alignment: getting people to converge on a defensible version without burning the timeline.

This is also where mentoring starts showing up. Even if you don’t manage anyone formally, you’ll often review junior drafts, give feedback, and set quality expectations.

If you want a clean way to benchmark compensation as you move into senior territory, one external reference I like for broad writing pay context is the BLS “Writers and Authors” overview. It’s not medical-writer-specific, but it gives you a baseline for how the market treats writing roles.

Once you hit principal/lead territory, the job becomes less about producing words and more about producing quality at scale.

This is where you’ll see writers owning standards, templates, QA checklists, and review workflows. You may also be the person who runs alignment calls, documents decisions, and prevents rework.

The biggest difference at this level is leverage. Your work improves the output of multiple people, not just your own drafts.

If you’re aiming for this, I’d start building credibility in one of two ways: either become the expert in a document type (and be the go-to person), or become the person who improves the team’s process so everyone ships faster with fewer errors.

[IMAGE: Senior vs Lead medical writer progression]

Medical writing career paths often fork here.

One path is management: hiring, coaching, workload planning, stakeholder communication, and quality programs. The other path is expert leadership: being the most senior individual contributor who owns complex deliverables, standards, and high-risk content.

Neither is “better.” They just reward different strengths.

If you like coaching, systems thinking, and scaling quality through others, management can be a great fit. If you like deep content ownership and you want to stay close to the craft, the expert path can be more satisfying.

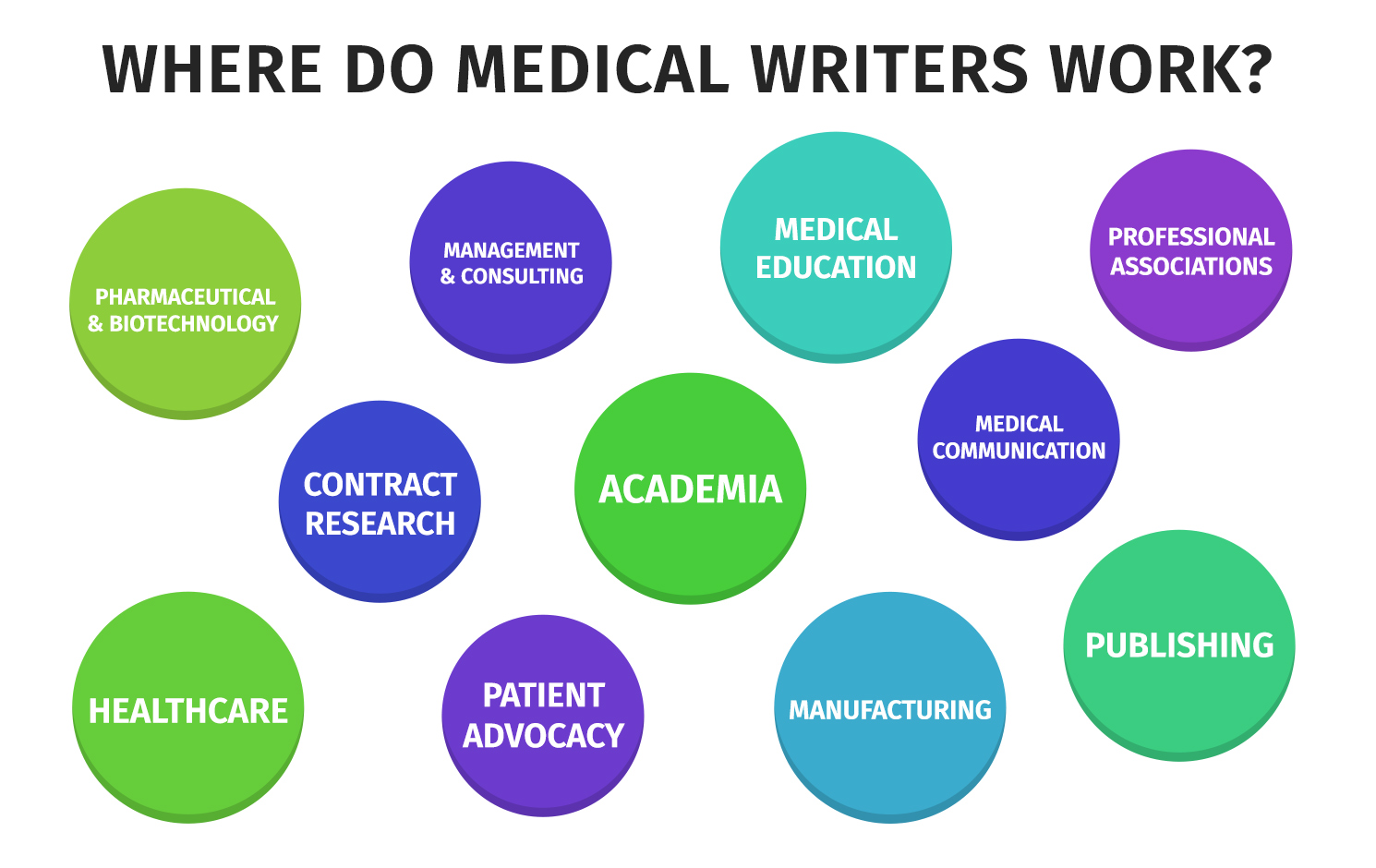

Freelancing is real in medical writing, but it’s not the “easy mode” people think it is.

The writing skill matters, but so does client communication, scope management, timelines, and protecting yourself from endless revisions. The writers who do well freelance usually specialize. They become known for a specific lane, document type, or therapeutic area.

If you want the freelance path later, I’d still start in-house or agency first if possible. You’ll learn how professional review cycles work, what “good” looks like, and how to handle stakeholder pressure without guessing.

No header here: If you want a medical writing career that keeps growing, don’t optimize for “more writing.” Optimize for trust. The writers who rise fastest are the ones who can take messy inputs, produce clean drafts, handle reviews calmly, and protect accuracy without drama.

Here are the most frequently asked questions about the medical writing career path.

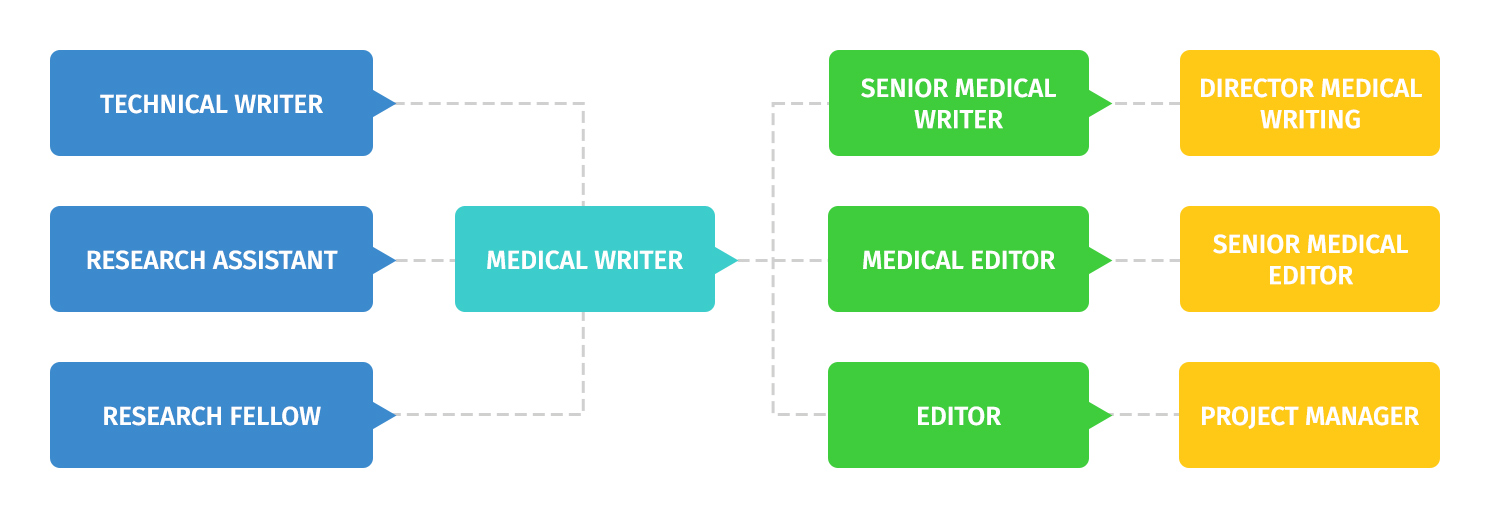

A common progression is Junior/Associate Medical Writer → Medical Writer → Senior Medical Writer → Lead/Principal Medical Writer. From there, many professionals move into people management (e.g., Medical Writing Manager) or strategy-focused roles (e.g., Editorial/Regulatory Lead, Scientific Communications Lead), depending on the organization and specialization.

Timelines vary by role type and industry, but it typically takes several years of consistent delivery across multiple projects, strong review performance, and demonstrated ability to work independently with complex content and cross-functional stakeholders.

Medical writing commonly branches into regulatory writing, clinical writing, medical communications, and publications. Each specialization involves different document types, audiences, and review standards, so specialization often depends on personal interest and the kinds of organizations a writer works with (pharma, biotech, CROs, agencies, or publishers).

Advancement typically requires strong scientific accuracy, editing discipline, stakeholder management, and the ability to lead document planning and review cycles. Senior progression also depends on strategic judgment—anticipating reviewer concerns, ensuring consistency across deliverables, and improving process quality over time.

Both approaches can work. Specializing early can accelerate expertise in a specific document type (such as regulatory submissions). Remaining a generalist can broaden exposure and make it easier to pivot. The best approach is usually the one that aligns with target roles and the market opportunities available.

Experienced medical writers often transition into medical writing management, regulatory strategy, clinical operations collaboration roles, publication planning, medical affairs, scientific communications leadership, or quality/compliance-related roles, especially when they have demonstrated process leadership and cross-functional influence.

If you are new to medical writing and are looking to break in, we recommend taking our Medical Writing Certification Course, where you will learn the fundamentals of being a medical writer, how to dominate medical writer interviews, and how to stand out as a medical writing candidate.

Get the weekly newsletter keeping 23,000+ technical writers in the loop.

Get certified in technical writing skills.

Get our #1 industry rated weekly technical writing reads newsletter.