Our reviewers evaluate career opinion pieces independently. Learn how we stay transparent, our methodology, and tell us about anything we missed.

Home › What is Documentation? The… ›

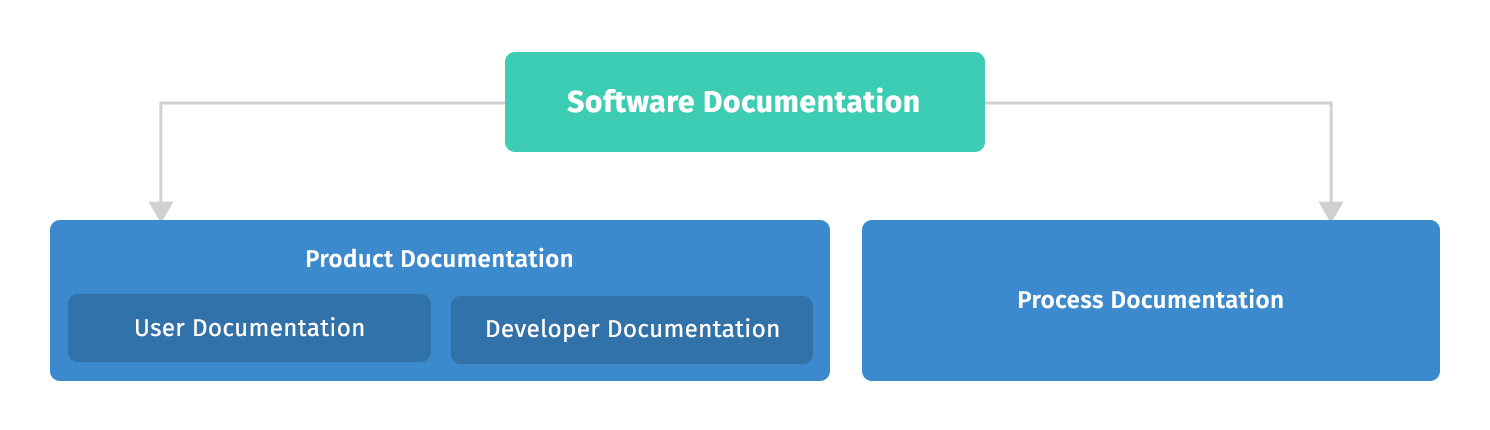

Software documentation is the written and visual material that explains how software works and how to use it. It includes user documentation, developer documentation, and internal technical documentation that supports planning, building, testing, and operating the software.

When software documentation works, it reduces confusion and speeds up execution. When it fails, teams fill the gaps with tribal knowledge, Slack messages, and guesswork.

Audience awareness is the biggest lever in software documentation. If you write one doc for everyone, you usually end up writing a doc that helps nobody.

End users want to complete tasks fast with minimal context switching. They benefit from setup guides, step-by-step instructions, screenshots that match the current UI, and troubleshooting steps that assume they are under time pressure.

I also keep language simple and direct, even when the product is complex. Clarity beats cleverness every time when someone is trying to get unstuck.

Developers read to implement, integrate, or debug. They care about accuracy, code samples, edge cases, and the smallest possible working example that proves the workflow is real.

If the doc includes API calls, I make sure the doc specifies required parameters, authentication, error responses, and a working request and response example. When teams need an external standard to align on tone and structure, I often reference Google’s developer documentation style guide.

Third-party developers are often working without your internal context, so documentation has to be more explicit. Integration docs should explain prerequisites, permissions, rate limits, version compatibility, and what to do when something fails.

I also pay attention to “integration drift,” where the product changes but old integration tutorials still rank in search or get shared in support macros. That is one of the fastest ways to create frustration.

Internal teams usually need documentation for coordination and consistency. Product managers want clarity around scope and decisions, support teams want repeatable answers, and engineering teams want architecture, configurations, and operational guidance that helps during incidents.

In enterprise environments, the documentation often needs stronger governance, access control, and review cycles because the cost of being wrong is higher. That is where having a clear owner and a predictable update protocol matters most.

Most software documentation falls into a few common categories. The trick is not naming them perfectly, it is making sure you have the right mix for your users and your team needs.

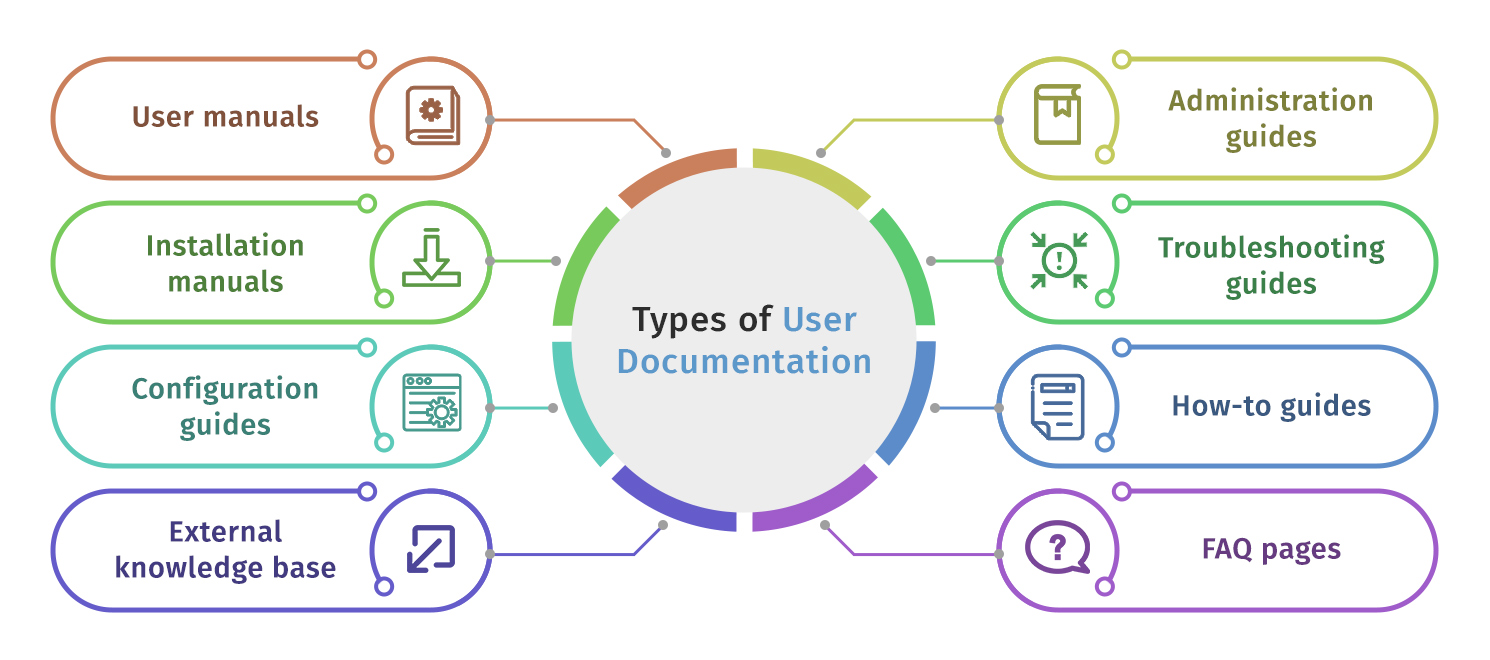

This includes user guides, user manuals, setup guides, tutorials, and help center articles. The goal is task completion, not conceptual depth.

If you want a structure that helps you avoid mixing content types, the Diátaxis framework is a useful external reference. It forces separation between tutorials, how-to guides, reference, and explanation.

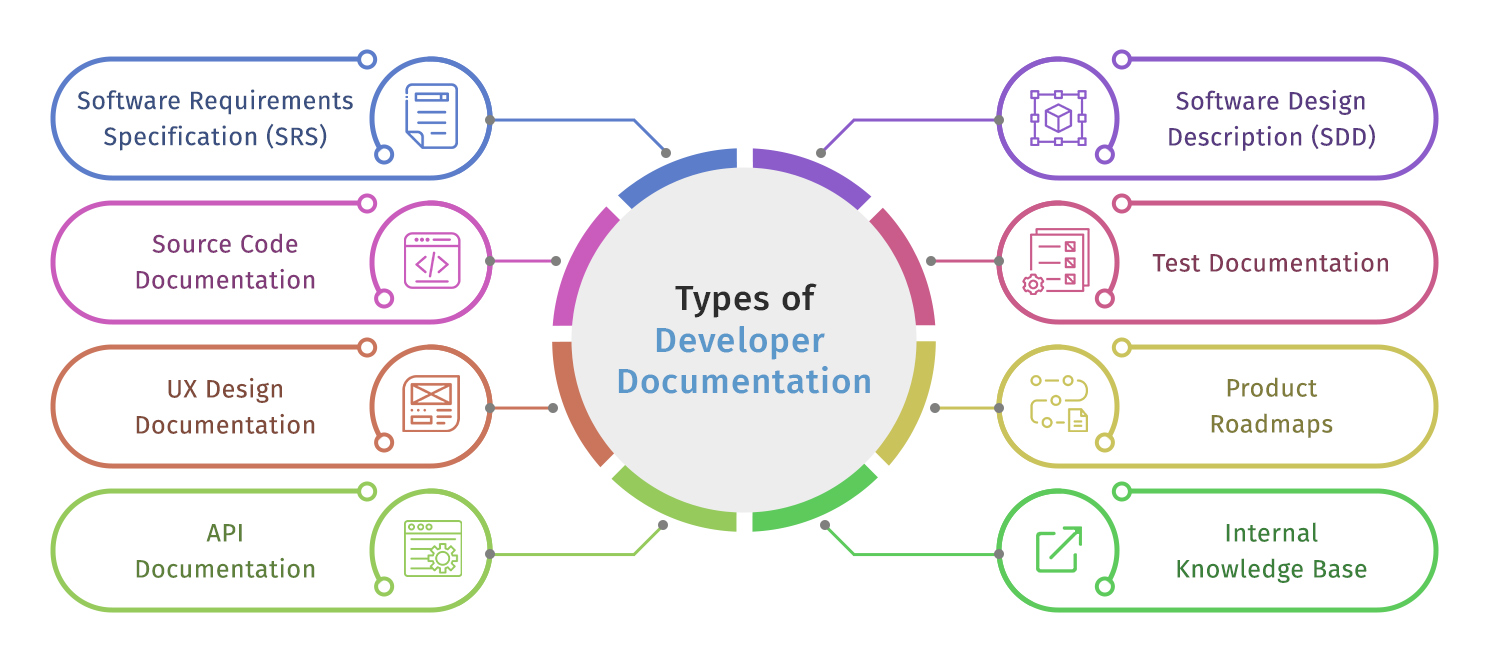

Developer documentation includes API documentation, SDK guides, integration docs, and developer onboarding documentation. These docs succeed when they are precise, example-driven, and versioned in a way that matches how the product ships.

I treat code samples as first-class content. If a code sample is wrong, the entire doc loses credibility.

This includes high-level architecture, low-level processes, configurations, technical specs, and operational runbooks. These docs help internal teams understand how the software behaves and how to support it under real-world constraints.

Architecture content is most useful when it answers “how the pieces fit” and “what depends on what.” I keep it focused so it stays maintainable.

Product requirements documentation and project documentation help teams align before building. This can include PRDs, technical design docs, decision records, and other artifacts that capture scope, tradeoffs, and constraints.

These docs are often the upstream source for user-facing documentation later. When requirements are vague, user docs usually become vague too.

Testing documentation includes test cases, testing procedures, quality assurance frameworks, and bug-tracking reports. These documents help teams validate behavior and reproduce issues without relying on memory.

I like test documentation that is written to be executed, not admired. If a test case cannot be run by someone new, it needs revision.

Release notes and changelogs communicate what changed and whether users need to take action. They work best when they link naturally to updated guides, updated reference content, or updated troubleshooting pages inside your docs set.

I treat release notes as a communication layer, not as the place where core instructions live. The core docs still need to be updated.

Code documentation includes source code annotations, docstrings, and README files that explain usage and intent. It is most effective when it is close to the code and reviewed alongside code changes.

A README that stays current is one of the fastest ways to improve developer onboarding. A README that is stale creates instant distrust.

Usability is where documentation stops being “content” and starts being “an experience.” I focus on findability, scannability, and confidence, because those are what users notice in the moment.

I use a clear table of contents for long pages and predictable headings that match user intent. I also avoid burying prerequisites and assumptions, because that is where most frustration starts.

If the doc lives in a tool like Confluence, I still enforce structure with templates and consistent headings. The platform does not solve usability on its own.

Templates reduce cognitive load for both writers and readers. When every page follows a similar pattern, users stop learning your docs layout and start learning your product.

I also keep a style guide so common terms stay consistent, especially in developer docs where naming drift creates confusion quickly. If you are building that baseline, Technical Writer HQ’s style guide examples can help you decide what to standardize first.

I use screenshots when the UI matters and when the screenshot reduces ambiguity. I do not use screenshots as a substitute for instructions, because screenshots go stale faster than text.

For complex workflows, short video tutorials can reduce friction, especially for onboarding. Tools like Loom can be useful for quick walkthroughs, but I treat videos as an addition, not the only source of truth.

For developer documentation, code samples are usable. A working sample reduces time-to-success more than a page of explanation.

I try to keep samples minimal and runnable. When possible, I include expected output so developers can confirm they are on track.

When I say “best practices,” I mean practices that survive real teams, real release cycles, and real constraints. These are the habits that keep software documentation clear, organized, and relevant.

I prioritize what the reader needs to do next. Then I add just enough context to prevent mistakes and reduce support load.

This approach keeps docs shorter and more usable, especially for troubleshooting and setup content.

I prefer small, frequent reviews over big, occasional rewrites. For fast-moving products, the safest strategy is to tie documentation updates to the same workflow that ships changes.

A lightweight content review checklist helps keep reviews consistent and prevents “looks good” approvals. The checklist also makes onboarding new reviewers easier.

Troubleshooting guides work when they address the failures users actually hit. I pull these failures from support tickets, bug reports, and engineering notes.

I keep troubleshooting steps concrete and observable. If the user cannot verify a step, it does not help them.

Release notes should tell users what changed and what to do next. They should not replace updates to the underlying guides and reference pages.

When you update docs, you also reduce future ticket volume because support can link to the right canonical page.

Image Source: projectsmart

Software documentation is rarely a solo activity. Collaboration is how you keep accuracy high and keep documentation aligned with the product.

I like a simple workflow: draft, SME accuracy review, editorial review, then publish. If the team is distributed, collaboration software and shared documents make this easier, but the process still needs clarity.

The key is to make roles obvious. Someone owns accuracy, someone owns clarity, and someone owns publishing decisions.

SMEs do not want to “write docs.” They want to validate what is true. I make reviews small, specific, and scoped to sections rather than asking for a full-document review.

This also improves speed in agile development environments, where waiting for perfect reviews slows releases.

Consistency collapses when many people write in many different ways. Templates and a style guide create a standardized knowledge foundation, even when multiple teams contribute.

This also improves onboarding because new contributors can follow a clear pattern without guesswork.

Version control is how you keep documentation trustworthy over time. Without it, teams lose track of what changed, why it changed, and whether the doc matches the product.

If your documentation is stored in GitHub alongside code, you can tie doc changes to pull requests and review cycles. This works especially well for API docs and developer onboarding documentation.

If your docs live in a docs platform, you still need version tracking and clear ownership. The tool should support revision history, approvals, and rollbacks if needed.

In continuous release environments, the goal is small updates frequently. I avoid giant documentation projects because they fail under constant change.

Instead, I focus on an update protocol tied to releases, then I run periodic audits on high-traffic pages to catch slow decay.

If you want an external resource that stays practical on docs workflows, tooling, and community practices, I recommend Write the Docs.

Troubleshooting content is where documentation proves its value under pressure. A good troubleshooting guide reduces time-to-resolution and prevents repeat support tickets.

I keep troubleshooting guides structured around symptoms, likely causes, and step-by-step fixes. For recurring questions, I create a dedicated FAQs section or an FAQ page that support teams can link to quickly.

If you want guidance on making troubleshooting content more usable, my guide on how I test documentation usability complements the approach well.

Software documentation is a system, not a pile of pages. When you tailor content to your audience, keep structure consistent, and build collaboration and version control into the workflow, the documentation stays useful even as the software changes.

If you want the fastest win, start with audience clarity and a simple update protocol tied to releases. Those two changes prevent most documentation from becoming stale.

Here I answer the most frequently asked questions about software documentation.

Software documentation is the set of written and visual resources that explain how software works and how to use, build, test, and support it. It can include user guides, API documentation, technical specs, test cases, and release notes.

Software documentation can serve end users, developers, third-party developers, customer support teams, and internal teams like product, engineering, and QA. The content should be tailored to the target audience’s goals and technical understanding.

Common types include user documentation, developer documentation, system documentation, product requirements documentation, testing documentation, release notes, and code documentation. Most products need a mix to support the full lifecycle.

Usable documentation is easy to find, easy to scan, and reliable. Clear headings, templates, a table of contents for long pages, accurate screenshots, and runnable code samples all improve usability.

Assign ownership, tie updates to releases, and use review cycles that fit your development pace. Version control and revision history prevent silent drift and make it easier to fix issues quickly.

Yes. Troubleshooting guides reduce time-to-resolution, and FAQs help support teams and users find common answers quickly. They also reduce repeat tickets when they are kept current and easy to navigate.

Get certified in technical writing skills.