Our reviewers evaluate career opinion pieces independently. Learn how we stay transparent, our methodology, and tell us about anything we missed.

Hiring managers love to say “you’ll write docs.” But I spend just as much time researching, interviewing subject matter experts (SMEs), and keeping docs alive after launch as I do writing.

When I got my first real technical writing job, the biggest hurdle was understanding the product. I was 23, writing software documentation for a video editing company, and I had to learn a whole new language fast. A big chunk of my week was getting engineers and SMEs to explain what they built in a way I could translate for real users.

More than a decade later, I have shipped documentation across a lot of industries. Tutorials, long-form manuals, quick reference guides, and internal playbooks. One thing I learned is that the pattern is always the same. The writing matters, but the process matters more.

So let me walk you through what the job looks like in practice, plus the career path, skills, training, and work environment most people do not understand until they are already in it.

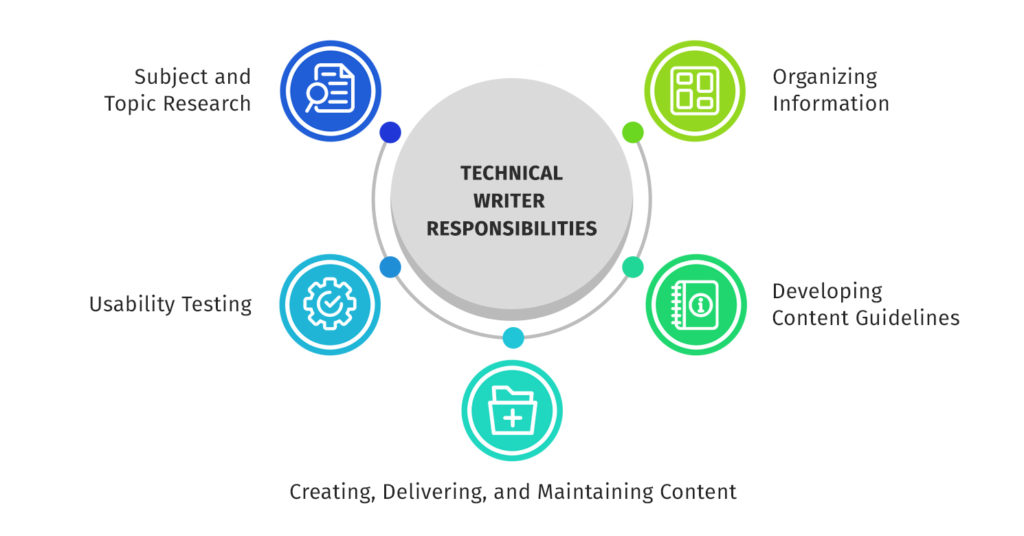

At a high level, a technical writer turns complex information into usable documentation for a specific audience. That might be end users, admins, developers, support teams, regulators, or internal employees.

The way I think about the job is simple. Learn the product fast, structure information so it is findable, and support the business by reducing confusion and friction.

With that in mind, here is what I actually do.

A lot of technical writing is relationship-building. I pull context out of engineers, PMs, designers, support reps, and solutions folks. I ask questions that feel obvious because “obvious” is where docs fail.

During my tenure with the video editing company, I sat with SMEs who spoke in terms like LUTs and color space while I was still translating the basics in my head. The only way I could learn fast was by asking the questions users are thinking but will not admit they have.

Even when I have access to SMEs, I still do my homework. My job is to synthesize, not transcribe. That research might include existing docs, support tickets, product requirements, competitor docs, user feedback, and release notes.

This is also where I start doing audience analysis. Who is the reader, what do they already know, what are they trying to accomplish, and what can go wrong. If I skip this, the doc sounds fine but fails in the real world.

Good technical writing is not “document everything.” It is “document what users need to succeed.” That means I make judgment calls about doc types and scope.

Is this a tutorial, a quick reference guide, a user manual section, a cheat sheet, or a technical specifications page. Does this belong in the docs site or in-app. Should it exist at all, or will support handle it better with a macro.

This step is basically content specification. I define what the doc should cover, and what it should not cover, before I start writing.

Docs have scope, timelines, dependencies, reviewers, and delivery dates just like product work. Before I write, I make sure I understand what is shipping and what is changing. Then I decide what gets updated versus what becomes a new page, because doc sprawl is real and it kills findability.

I also set review expectations early. Engineering owns technical accuracy, product owns workflow and UX alignment, and legal or compliance gets involved when wording carries risk. Once you are planning multiple doc streams across releases, you start looking like a documentation manager because you are running content ops even if your title does not say it.

Technical writing rewards the opposite of ego. My default is short sentences, explicit steps, consistent terminology, and examples that match what the user is trying to do. If a sentence can be misread, it will be misread, usually by someone tired and under pressure.

Clarity also means being strict about language. If the UI says “Create workspace,” I do not call it “set up an environment.” If a parameter is timeoutSeconds, I do not casually refer to it as “timeout.” Small inconsistencies create big confusion across a doc set.

If you want the cleanest how-to breakdown of the writing side, here is the guide I point most people to: how to write software documentation in 7 simple steps.

A big part of my job is information architecture even if my title does not say it. That includes navigation structure, page naming, “related articles,” templates, and making sure the docs do not turn into a graveyard of random pages no one can browse.

When documentation gets messy, it is rarely because the writing is bad. It is because the structure is bad. Duplicate pages, outdated articles that still rank in search, inconsistent titles, and scattered workflows are what make users stop trusting docs.

Most teams do not realize how quickly docs drift. Feature names change. UI labels change. Screenshots go stale. Workflows change. Terminology becomes inconsistent across teams.

So I spend a lot of time editing, maintaining a glossary, and enforcing standards. That includes voice, formatting, and “how we describe things here.” It is not glamorous, but it is the difference between docs that scale and docs that rot.

If you want to learn more about the technical writing process, check out our Technical Writing Certification Course.

Publishing docs is easy. Maintaining them is hard.

Post-launch, I watch for changes that quietly break documentation. New UI, new permissions, updated integrations, backend changes that affect outputs. If docs get outdated, users stop trusting them, and once trust is gone it is hard to get back.

This is also why peer reviews and editorial reviews matter. When a team has a real maintenance cadence, the docs stay aligned with reality rather than becoming “something we wrote once.”

Modern technical writing is usually done inside a documentation platform. Sometimes docs-as-code, sometimes a knowledge base, sometimes a CMS, sometimes a mix.

So part of my day looks like:

This is why “tech-management pro” is a real requirement for many technical writing jobs, even when the job description pretends it is just writing.

The title “technical writer” can mean a lot of different things. One company needs an API documentation writer. Another needs a technical documentation specialist for internal SOPs. Another needs a UX writer. Another needs hardware installation manuals.

The fastest way to grow your career is to get clear on the flavor of role you want, then build evidence you can do it. Portfolios beat vibes. A writing assessment is easier when you already have samples that look like the job.

If you want a benchmark for real hiring expectations and responsibilities, check technical writer job description examples.

If you want strong proof-of-work patterns you can copy, check the top technical writing portfolio examples.

If you’ve never worked on a mature docs team, this part can surprise you. A lot of people imagine technical writing as “I open a doc and type.” In reality, most of my output comes from the process around the writing.

The easiest way to explain it is a document development life cycle. Different companies name the phases differently, but the workflow is the same.

First is information gathering and planning. This is where I pull inputs from everywhere. I interview subject-matter experts, but I also look at supporting documents like product requirements, technical specifications, support tickets, bug reports, and customer feedback. If the product team has product samples, staging environments, or test accounts, I want those too, because nothing beats validating steps yourself.

Then I do audience analysis and user task analysis. Audience analysis is about context. Who is reading this, what do they already know, and what terminology do they use day to day. User task analysis is more practical. What are they trying to do, what blocks them, and what mistakes do they tend to make. This is the difference between a doc that sounds correct and a doc that actually helps.

Next is content specification. This is where I decide what we are building. Is it a how-to guide, an instruction manual section, a quick reference, a troubleshooting page, a set of release notes, or a technical specifications page. I’m also deciding what not to build, because doc sprawl kills findability.

After that is content development and implementation. This is the writing part, but it includes structure and information architecture too. Where does this live in the nav. What’s the page title. What related pages should the reader see next. What terms need a glossary entry. This is also where internal corporate style guides come into play, because consistency is a product feature in documentation.

Then I run technical and editorial reviews. Technical review is about correctness and risk. Editorial review is about clarity, tone, and consistency. This is where I’m thinking about things like product liability specialists getting involved when wording could create safety, legal, or compliance issues. On the flip side, customer-service managers and support leads are great reviewers when you’re writing anything that affects tickets, macros, or escalation workflows.

Next, formatting and publishing. Sometimes that is docs-as-code in Git with PRs. Sometimes it’s a CMS workflow. Either way, I treat publishing like a release. Versioning matters. Labels matter. And if you work on regulated or enterprise documentation, you’ll also run into formal documentation standards. In some industries that includes ATA100 (aviation) or S1000D (defense). In software, teams often reference the Microsoft Manual of Style for technical publications, or they create an internal style guide based on it.

The last phase is maintenance, and it is never optional. Docs are not a one-time project. They are a living system. If you want to level up fast in this career, get good at building a repeatable life cycle and then keeping it running across releases.

If I were breaking in today, I would focus less on titles and more on the environment. You want a place where documentation is visible, feedback is frequent, and you can learn the product through real work. Job boards can help, but professional networking sites like LinkedIn and professional communities tend to create warmer leads.

First, I’d treat LinkedIn like a portfolio funnel, not a resume dump. I’d post small “documentation breakdowns” of real things I’m building. A short thread on how I turned messy SME notes into a clean how-to guide. A before-and-after showing how I removed industry jargon and made steps testable. Hiring managers don’t need perfection. They need evidence you can think.

Second, I’d use professional communities as my feedback engine. You can get better in weeks if you consistently ask for critique from working writers. I’d also do informational chats over videotelephony platforms like Zoom or Google Meet, because a 20-minute call can do more than 50 cold applications. You don’t have to beg for a job. You can simply ask how their docs team works and what kind of writing assessments they use.

Third, I’d be strategic about where I apply. Job boards are fine, but they are noisy. I’d still use them, but I’d bias toward environments where documentation is respected. Look for signs like dedicated doc owners, structured reviews, clear release cadences, and a real docs site. Those environments teach you faster.

Online courses and workshops can help, but only if they produce real output. The best “course” is the one that forces you to ship an actual deliverable and revise it after feedback. That revision loop is basically the job.

One more thing. Don’t underestimate adjacency. Some of the strongest “breaking in” paths come from roles like support, QA, implementation, product ops, or even training. If you’re already close to the product and users, you’re halfway to being a technical writer. The skill you’re adding is technical communication. Turning what you know into documentation other people can use.

Many technical writers have a bachelor’s degree, but the degree itself is rarely the main differentiator. What matters is your ability to learn quickly, write with clarity, and handle review cycles like a professional.

On-the-job training is huge in this field. So are peer reviews, editorial review, and learning how to work with SMEs. If you want a more formal signal, professional organizations can help. The Society for Technical Communication is one of the better-known professional organizations in the space, and it can be a good way to find mentorships and professional credential options: Society for Technical Communication.

Technical writers show up everywhere. Software documentation writer roles often include APIs, SDKs, and platform docs. Hardware documentation writer roles can include installation guides and service manuals. Medical or pharmaceutical writer roles can include regulated documents and submission support. Some writers drift into e-learning and training content, localization and technical translation workflows, or information architecture-heavy documentation programs.

Specializing is how a lot of writers level up. Once you can handle complex projects and become the “go-to” person for a domain, you become harder to replace.

Most technical writing careers look linear on paper, but the real progression is about scope.

Early on, you are usually focused on execution. You’re writing how-to guides, updating instruction manuals, cleaning up workflows, and learning how to interview subject-matter experts without wasting their time. The biggest win at this stage is becoming reliable. You can take ambiguous inputs and ship something clear.

Mid-level is where you start owning doc streams end-to-end. That means you are not just writing pages. You are deciding what documentation should exist, aligning with product designers and PMs on UX and workflow, and coordinating reviews like a mini project manager. This is also where you start touching more complex projects, like migration guides, admin workflows, or cross-feature documentation that spans multiple teams.

The senior technical writer jump usually happens when you can handle higher-risk content and higher ambiguity. Think technical specifications, platform docs, or anything that can break production if misunderstood. You can run multiple doc tracks across a release. You can look at a doc set and fix the information architecture, not just the wording.

Senior is also where mentorship becomes real. You’re reviewing drafts, training junior staff, and setting standards so quality scales across the team. If you want to accelerate your growth, find mentorships early and then pay it forward once you’re stable. Teaching is a fast way to expose your own gaps.

From senior, you usually pick a direction.

One path is the expert individual contributor route. Titles vary, but the work becomes more specialized. You might become the “API person,” the “hardware person,” the “regulated docs person,” or the writer who owns the hardest integrations. This can be a great path if you like deep domain knowledge, technical communication strategy, and being the go-to person for complex projects.

The other path is leadership. That might look like documentation manager, content ops lead, or program owner. You’re defining processes, staffing, roadmaps, and tooling. In practice, you’re running a documentation function like a product team.

And then there’s freelancing. Freelance opportunities tend to increase when you can articulate your niche and show proof of work. The writers who do best as freelancers usually pick a lane. For example, “I help B2B SaaS companies ship better onboarding docs,” or “I write technical specs and supporting documents for regulated products.” The clearer the niche, the easier it is to price and to sell.

One last note on industry trends. The career is expanding. More companies expect writers to collaborate on media production (like training videos or interactive tutorials), knowledge management, and even light enablement. You don’t have to do all of that to grow, but being aware of where the field is heading helps you choose your next skill on purpose.

If you want a grounded view of pay and projected growth, I point people to government data first, then layer in industry context. The BLS technical writers page is the cleanest starting point.

If you want more granular salary data by state and area, use the OEWS tools: Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics data.

Most technical writers work in collaborative environments with lots of dependencies. You will spend time in meetings, reviewing comments, and coordinating with SMEs. Deadlines are real, and in some teams, you will occasionally work evenings and weekends around launches.

The good news is flexibility is common. Remote work and flexible office arrangements show up frequently, especially for software teams. The hard part is learning to stay organized while juggling multiple reviewers, shifting priorities, and a toolchain that includes content management systems, ticketing systems, and publishing workflows.

Here are the most frequently asked questions about what a technical writer does:

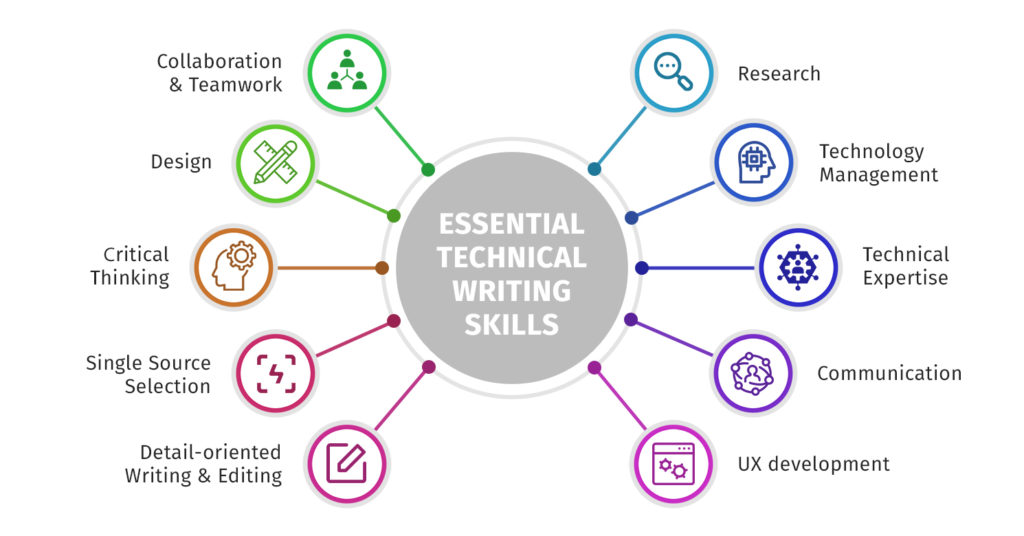

The core is clarity. Everything else supports it. You need strong audience awareness (who is this for and what are they trying to do), attention to detail, and the ability to hold context in your head while you write. Critical thinking matters because you are constantly deciding what to include, what to exclude, and what the user needs first. Solid grammar and style help, but revision skills matter more because most docs become good after two or three rounds of rewriting. Research skills and light subject matter expertise are also essential because you will never be the smartest person in the room, but you still need to produce accurate content.

A simple “career test” is whether you enjoy making confusing things usable. If you like asking questions, organizing information, and writing with purpose instead of personality, you will probably like technical writing. If you hate feedback, get bored by precision, or want your writing to be expressive, the job can feel restrictive. The best way to test fit is to create one real how-to guide from scratch using messy inputs, then revise it after someone else tries to follow it. If you enjoy that process, you are in the right neighborhood.

Senior technical writers tend to take ownership of complex projects, not just individual pages. They plan documentation like projects, manage timelines and reviewers, and make decisions about information architecture across a doc set. They also get trusted with higher-risk content like technical specifications, migration guides, and workflows that can break production if misunderstood. Another big shift is mentorship. Senior writers often review drafts, train junior staff, and improve standards so quality scales. If you want faster advancement, lean into project management, cross-team communication, and the ability to ship reliable documentation under changing requirements.

A bachelor’s degree can help, but it is rarely the deciding factor. Hiring managers care more about whether you can write clearly, learn quickly, and show proof through a portfolio. Certifications can be useful if you are switching careers and need a credibility signal, but they do not replace real samples. What matters most is training that produces output: a writing assessment, peer reviews, editorial review practice, and on-the-job exposure to SMEs and real workflows. Professional organizations can also help with mentorships and community support, especially early on.

Start by building a small portfolio that looks like real work: one how-to guide, one quick reference guide, and one “troubleshooting” style page based on a product you can access. Then use LinkedIn and professional communities to get feedback and make connections, because warm intros often beat cold applications. Job boards are fine, but also look for adjacent roles where writing is part of the job, like support, QA, implementation, or customer success. The key is to prove you can translate industry jargon into clear steps and handle revision without ego.

The biggest one is scope control. New writers often try to document everything instead of documenting what the audience needs to complete a task. The second is SME management, because subject-matter experts may be busy, inconsistent, or assume too much context. Another common struggle is writing without real product access, which makes it harder to validate steps and capture accurate supporting documents like screenshots or sample outputs. Finally, many new writers underestimate project management and audience analysis. Good docs are not just writing. They are information gathering, structured delivery, and continuous revision as products change.

If you are new to technical writing and are looking to break in, we recommend taking our Technical Writing Certification Course, where you will learn the fundamentals of being a technical writer, how to dominate technical writer interviews, and how to stand out as a technical writing candidate.

Get certified in technical writing skills.