Our reviewers evaluate career opinion pieces independently. Learn how we stay transparent, our methodology, and tell us about anything we missed.

Hiring yourself into a new career is awkward, especially when you’re leaving a role you’re genuinely good at. If you’re an English teacher eyeing technical writing, I’ll walk you through what changes (and what doesn’t), plus the exact steps I’d take to get hired.

I’ve been around technical writing for a long time, and I’ve done it in environments where the stakes were very real.

Also, a lot of “teacher to technical writer” advice online is fluffy. It’s usually some version of “learn Markdown and apply.” That’s not wrong, but it’s incomplete. The real transition is about responsibility, deadlines, and being flexible when the work changes mid-sprint (because it will).

Okay, let’s get into it.

You’re not starting from zero. You’re repackaging what you already do well, learning a new context, and proving it with a portfolio.

Here’s how I’d break down the transition, the same way I’d coach a friend through it:

With this roadmap, you’ll have a clear strategy to transition into technical writing while leveraging the skills you already excel at.

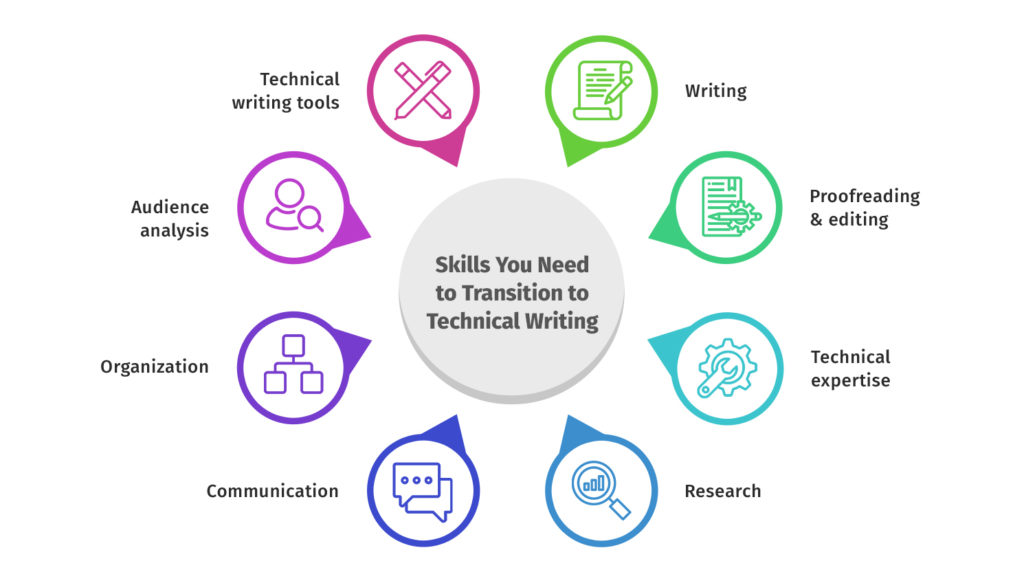

If you’ve taught high school education (or any grade, honestly), you already have a strong foundation for technical communication. The key is to stop describing yourself like a teacher and start positioning yourself as a technical communicator. Here’s how your teaching skills translate directly to technical writing:

If you want a clearer picture of the role you’re stepping into, I’d read my guide on what a technical writer does day to day.

The mindset shift is subtle but important: you’re not “just a strong writer.” You’re someone who can design understanding.

A lot of teachers imagine technical writing as “writing about technology.” Sometimes it is. Most of the time, it’s “owning clarity in a messy environment.”

Here’s what technical writers do in the real world:

When I was early in my career, the hardest part wasn’t writing. It was learning how to ask better questions.

Teachers already know how to do this. You probe, you clarify, you listen for what isn’t being said, and you adjust your explanation based on the person in front of you.

That’s also why tech writing shows up in so many environments: web-based products, internal platforms, academic institutions building research tools, STEM education programs, and science-based organizations that need documentation plus precision.

If you’re coming from teaching, the biggest surprise is this: technical writing is collaborative and iterative. You rarely “finish” a doc once. You maintain it. And that’s why adaptability matters so much, which brings me to the next section.

This is the part nobody wants to talk about because it’s less “fun” than tools and portfolios, but it’s the real transition.

Teaching is demanding, but it’s structured. You have bells, semesters, a predictable rhythm, and you control your classroom. Technical writing, on the other hand, is professional chaos with deadlines.

You’ll juggle multiple responsibilities at once. You might be writing docs, reviewing UI copy, answering support questions, and cleaning up an internal knowledge base in the same week. Some teams expect you to run content management processes, not just write pages.

For example, in teaching, deadlines are often calendar-based. In tech comm, deadlines are dependency-based. Engineering ships, so the docs ship. If a release date moves, your documentation plan moves with it.

As a technical writer, you also have more ownership than you might expect. In many orgs, the technical writer becomes the person responsible for “the truth” of how a product works. That’s a heavy responsibility, and it’s why your flexible mindset matters.

This shows up even outside software. If you write for science-based organizations, you might support grant writing, research documentation, or internal process documentation. In academic institutions, you might document tools used by faculty or students, where accuracy and accessibility matter a lot.

So here’s the adaptability framework I suggest:

If you want a bigger-picture roadmap beyond the teacher transition, our guide on how to become a technical writer without experience is a strong companion read.

Most teachers I talk to don’t doubt their writing. They doubt their “technical” credibility.

That’s normal. It’s also fixable. Confidence in technical writing usually comes from three places: repetition, feedback, and context.

You don’t need to master everything at once. The goal is to familiarize yourself with what exists and build competence over time.

If you’re coming from a teaching background, you already know that rhetoric and intercultural communication matter. In documentation, it shows up in audience recognition: who is reading, what they know, and what tone they expect.

One confidence trick I’ve used for years: treat every doc like a lesson plan. The reader is your student. The interface is your classroom. Your job is to reduce confusion.

That framing calms the imposter syndrome fast because it puts you back in a role you’re already good at.

A portfolio is the fastest way to make a career change feel “real” to hiring managers. It’s not about perfection, it’s about proof.

If I were building a teacher-to-technical-writer portfolio today, here’s what I’d include:

The biggest portfolio mistake I see is making it too academic. Teachers sometimes write like they’re trying to impress an evaluator. In tech comm, you’re trying to help a user complete a task.

If you want to see what strong portfolios look like (and how broad “portfolio” can be), check out these technical writing portfolio examples.

And yes, keep it lightweight. A few strong samples beat a bloated folder of half-finished docs.

Networking doesn’t mean walking into a room and handing out business cards like it’s 2006. It means building a network of people who can give you context, feedback, and referrals.

Here’s what I’d do:

One more thing: when you reach out, lead with what you’re building, not what you want. “I’m transitioning and I built a small product documentation sample, could I get feedback?” is far more effective than “Can you help me get a job?”

Let’s make this practical.

Some technical writers have degrees in English, communications, journalism, or related fields. Others come from technical degrees. A lot of hiring teams care less about the major and more about whether you can do the work.

That said, a few qualifications can make your transition smoother:

If you’re applying to teams with mature documentation practices, they may look for familiarity with content management systems, versioning workflows, or structured writing approaches. Don’t panic if you don’t have that yet. You can learn it.

What I’d ignore early on:

If you can write clearly, learn quickly, and operate responsibly under deadlines, you can transition. And honestly, teachers are better at the “responsibility” part than they give themselves credit for.

Transitioning from English teacher to technical writer can feel like stepping into a new world, but the core skill is still the same: you help people understand something that was confusing five minutes ago. If you build a small portfolio, practice adaptability, and get real feedback, you’ll be in a strong position to land your first role.

Here are the most frequently asked questions about “English teacher to technical writer transition”.

Yes. English teachers often have strong transferable skills such as clear writing, audience awareness, lesson planning, and communication. These skills map well to documentation work, especially when combined with a portfolio showing technical writing samples.

Emphasize transferable skills (writing, editing, curriculum planning, stakeholder communication), include documentation-related projects you created independently, and link to a portfolio with writing samples that demonstrate instructional clarity.

A certificate is not always required, but it can help career changers learn common workflows, tools, and documentation standards faster. Employers typically value portfolio quality and relevant experience more than credentials alone.

Common entry-level deliverables include how-to articles, quickstart guides, knowledge base content, FAQs, release notes, and internal documentation. Responsibilities vary by company and industry.

Start with industries connected to your interests or background, such as edtech, STEM education, academic institutions, healthcare, or software. Review job descriptions and build portfolio samples that match the document types those roles require.

Timelines vary. Many career changers can become job-ready within a few months if they consistently build portfolio samples, learn core documentation practices, and actively network. The key factor is producing proof of skill, not time spent reading about the field.

If you are new to technical writing and are looking to break into the industry, we recommend taking our Technical Writing Certification Course, where you will learn the fundamentals of writing and managing technical documentation.

Get the weekly newsletter keeping 23,000+ technical writers in the loop.

Get certified in technical writing skills.

Get our #1 industry rated weekly technical writing reads newsletter.